But then something strange happened: Australia forgot.

While Diggers who fell on the battlefields of World War II are remembered and venerated each Anzac Day, the 26 souls who died at the Kapooka army training camp on May 21, 1945, were quietly airbrushed from the Anzac story. Their terrible fate was excluded from the official histories of World War II and has all but vanished. "Though the tragedy lives on in local memory and in the minds of the victims' families, it has disappeared altogether from national memory," says Peter Rushbrook, senior lecturer at the Wagga Wagga campus of Charles Sturt University and one of only two historians to have studied the accident. As the nation prepares to commemorate another Anzac Day, those who died at Kapooka are the forgotten dead. "They had signed up and they were prepared to give the ultimate sacrifice, so it is wrong that they should be forgotten," says Norman Degrandi, an army sapper at the camp at the time of the disaster.

So what happened at Kapooka and why did a country that reveres its Anzacs forget their sacrifice?

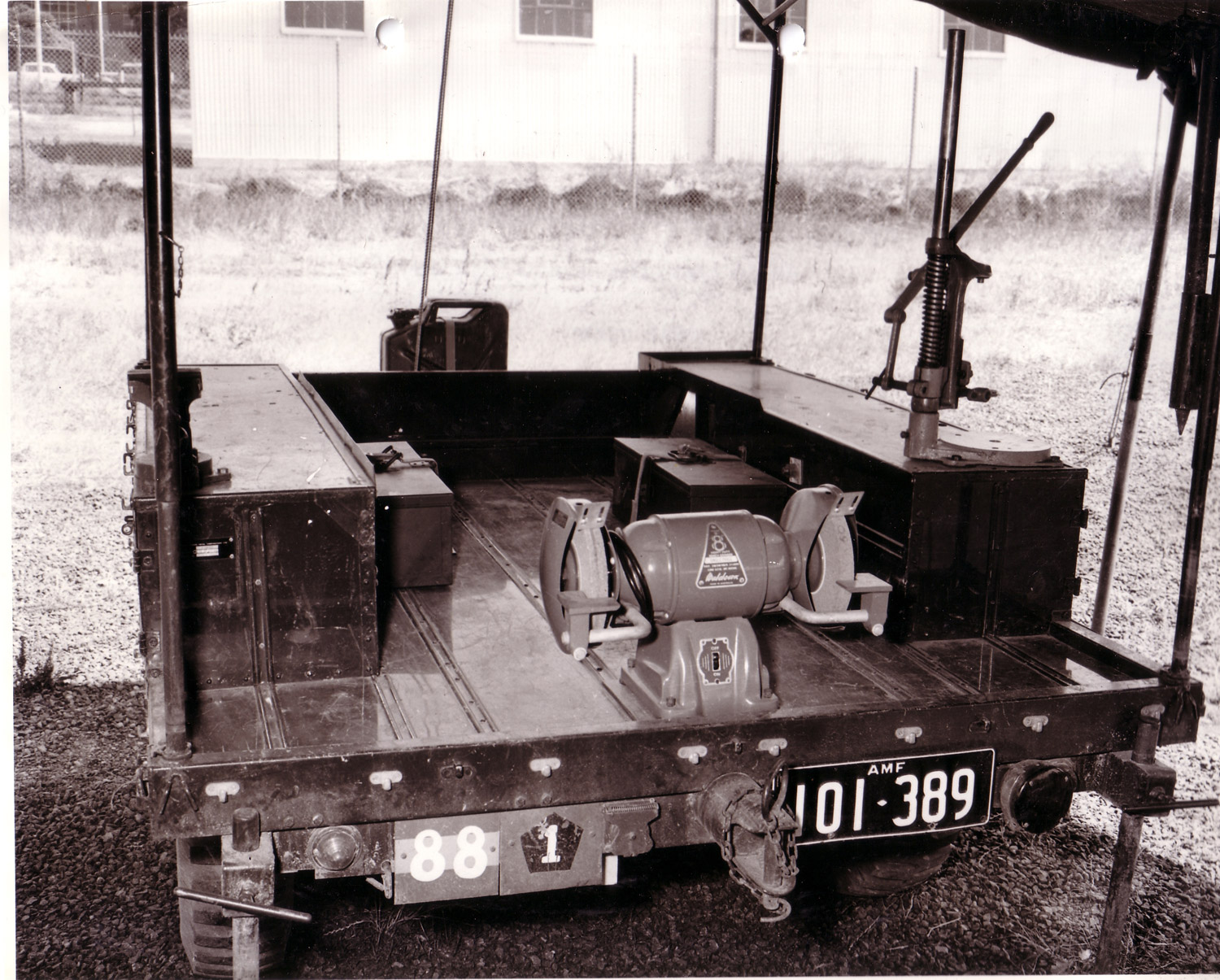

The day of the accident began like any other at the Royal Australian Engineers Training Camp, a rough bush base where long rows of tents were home to several thousand young army recruits. In Europe, Hitler's Germany had been defeated but the war against Japan was still raging and the Kapooka recruits were to be sent overseas once they had completed their engineer training. It was week four of the 16-week training program, a period known as demolition week because the young trainee sappers would be taught how to set and detonate explosives. It was also the 31st birthday of one of the instructors, sergeant Herbert "Jack" Pomeroy, a veteran of the Middle East and New Guinea campaigns and father of four children under the age of five.

Pomeroy was bored with instructing and wanted to return to the front line. But having worked in an explosives factory he was considered a "conscientious and solid instructor" for the trainee sappers. On the afternoon of May 21, Pomeroy led 26 young men out into a paddock and down some steps into a large but rudimentary underground dugout where Pomeroy held his lectures. The covered dugout was 6.4m long, 5.8m wide and 2.1m high at its centre, its roof roughly level with the ground outside. Bush timber supported the walls and ceiling, sawdust covered the floor and the soldiers sat around the edges on old ammunition boxes.

They were young, mostly teenagers. Before joining the army they had worked as farmhands, tractor drivers, motor mechanics, milk factory workers, timber cutters and barbers. Sitting alongside these young recruits was a deadly cache of explosives. "On that day a considerable quantity of explosives had been stored inside: a total of 100lbs (45.4kg) of monobel and 10lbs of gelignite, plus a large quantity of detonators and fuses," says military historian David Mitchelhill-Green, who examined the Kapooka tragedy only after a chance discovery in the National Archives last year alerted him to the tragedy.

Having explosives and detonators in the same dugout was routine. It was not considered risky because it seemed inconceivable that the detonators could accidentally come into contact with the explosives, which were stored on the far side of the dugout.

On this day, Pomeroy began his talk on the preparation of hand charges, demonstrating how to cut and crimp safety fuse wire, attach it to a detonator, then place the detonator into a tennis ball-size plug of monobel

As he spoke, another instructor, sergeant Kendall, left the dugout to complete a task. Kendall was walking back towards the dugout when a massive explosion and a wave of searing heat knocked him to the ground. He knew what had happened.

"From my position on the ground I could see that the roof of the dugout had caved in and a portion of a man's body had been blown to a position close to me," Kendall recalled at the time.

Elsewhere across the camp, soldiers assumed the blast was a part of training and it took several minutes for them to register what had happened

One soldier, sergeant Tafe, saw smoke and debris filling the air above the dugout and raced towards it.

"A grisly scene confronted him," Mitchelhill-Green says. "Checking the mass of bodies for signs of life, he found sapper Allan Bartlett in an upright position, imbedded into the southwestern wall by the force of the blast."

Miraculously, Bartlett was alive. Two other soldiers in the dugout were also alive but they died within hours from horrific wounds.

One rescuer observed seven intact bodies seated against the wall with their arms folded. "They looked like men of 80, their faces ash grey," he said.

The others were blown to bits. "Nineteen were identified by identity discs," says Rushbrook. "The remaining seven, being unrecognisable, were identified through personal possessions, including wedding rings, dental records and labelled clothing, including braces and civilian underwear. Pomeroy was identified by his engraved watch."

Having survived the explosion, Bartlett was able to give evidence to the subsequent military inquiry from his hospital bed

"He described how (another instructor) corporal Cousins was holding a handful of detonators with blue fuses attached before the blast but was right on the other side from where the explosives were," says Mitchelhill-Green. Bartlett said he had turned to "say something to my mate" and the next thing he recalled he was being "dragged out of the hole".

The army was stunned by the carnage and released a short statement that day saying 26 men had been killed in an explosion and promised an immediate inquiry.

Although the country was distracted by the war overseas, the Kapooka tragedy was front-page news and nowhere more so than in the nearby town of Wagga Wagga. A mass funeral for the victims was held there three days later.

"A lorry of wreaths and four flag-draped semi-trailers carrying the coffins crept sombrely past half of Wagga's 14,000 population," says Rushbrook. "After separate denominational funerals, the coffins were lowered simultaneously into the prepared graves. The emotion of the event continues to reverberate in local memory."

The government and the media vowed that Kapooka would not be forgotten.

Agriculture minister E.H. Graham said the sappers had "given their lives in the cause of freedom just as assuredly as if they had fallen on the battlefield. We will remember them with gratitude and, by honouring them, honour ourselves."

Wagga's Daily Advertiser newspaper stated: "Once in uniform, a person is a soldier of the king and, should death come swiftly in peaceful surroundings far removed from the battlefront, a life has been given for the king as surely as if the soldier had died in combat."

But these promises quickly faded. Unlike those who gave their lives on the Kokoda Track or in the deserts of North Africa, there was no national pride in remembering an explosives accident in rural NSW. It was a tragedy that did not fit the Anzac narrative, and, as such, it was not consigned to history.

"As far as I am able to ascertain, there has been no previously detailed published account of the Kapooka tragedy," says Rushbrook, whose account is to be published in the journal of the Australian and New Zealand History of Education Society.

"The official history of World War II makes no mention of it, nor does the Australian Centenary History of Defence. The only monuments to the event are a mouldy plaque at the site, now privately owned and locked to the public and a modest memorial at Wagga's war cemetery."

A brief military inquiry explored the tragedy and could find no conclusive cause as to how or why detonators might have made contact with the explosives. It was speculated that an instructor holding a detonator might have tripped. To prevent a repeat tragedy, the army prohibited the use of detonators in the same dugout as explosives.

Rushbrook says that in the years since, the Kapooka tragedy has been consigned to "quiet oblivion". "Social memory and heritage favours those who die valiantly," he says. "There appears to be a public awkwardness, even shame, when lives are taken 'without honour'. The national machine that creates and reinforces heritage, in these cases, remains silent."

Mitchelhill-Green agrees. "This was an awful event that does not sit comfortably in our paradigm of wartime death," he says. "The Anzac legend has become distorted over the years. We forget those soldiers who died during their training in Australia but their deaths are as poignant as those on foreign fields."

Des Surkitt was a young sapper at the Kapooka camp who lost several mates in the blast and had to pack up their personal possessions and send them back to their families. "It was a terribly upsetting time," Surkitt says.

For the next half-century he heard nothing more about the tragedy.

"Then one day I was listening to Macca (Ian McNamara, on ABC radio) and they said there was going to be a memorial service in Kapooka," he recalls. Surkitt jumped into his car and drove north from his home in Victoria to attend what was then the 50th anniversary of the tragedy.

Among the "few hundred" mourners in attendance was the only surviving sapper, Bartlett, who was by then profoundly deaf. The last direct connection to the Kapooka tragedy has since passed away.

"It was no fault of their own that these boys died," says Degrandi. "We should remember them. We owe them that."

Cameron Stewart is The Australian's associate editor.